November 25, 2022

Soursop and Ponies in Kona: A C++ Committee Trip Report

Earlier this month, the C++ committee meeting had its penultimate meeting of the C++23 cycle. It was also the first in-person meeting of the C++23 cycle. This means that C++23 was mostly designed over zoom. Which, sadly, explains in part why the language side of things has been rather stagnant these past couple of years.

But a lot of things happened in Kona. I forgot how intense these things were. Despite operating on 4 or 5 hours of sleep every night, the week flew by very fast. I also missed a lot of important discussions, as I have yet to develop the ability to be in several rooms at once.

To get an overview of things you can check out the traditional Kona Trip report on reddit and the list of papers moved at this meeting.

If you want my more personal takes on what happened, you are in the right place.

It’s been a while!

The meeting was held in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. It was the first in-person meeting since the zombie apocalypse.

But Hawaii is far away (a statement that is true no matter where you live) and not exactly cheap.

So a large part (around half or so) of the attendance, was remote. I will be honest, I expected that to be a disaster, but it went pretty smoothly. In particular, the tech worked well!

Thanks to the organizers to make that experience viable. Thanks to people who stayed far into the night on zoom to participate in the discussions, and most of all, thanks to the great people of Hawaii for having us.

Some would like more of the work to be remote. I also think more of the work should be not only remote but also asynchronous. The model of presenting a paper and immediately having people voice opinions before they could weigh the ins and outs isn’t always productive.

At the same time, speaking as a pretty introverted person, there is value in having the opportunity to exchange ideas with people, have 1-on-1 conversations and get a better view of the big picture, rather than talking about a specific paper every week or 2, in an order that rarely makes sense. A lot happens outside of the actual meetings.

There is also value in the time and energy commitment that everyone is able to make. As it turns out until they ship you in a plane and forgot about you for a week, companies let people work on C++ things if there is nothing else more pressing to do; there is always something more pressing to do. Meeting weeks are an opportunity for people to shift their focus and energy on C++ exclusively, so things move faster.

They are also very intense weeks, with long days. I was up and running from 6 am to midnight every day, and I’m still trying to recover!

The downside is that, with 5 or 6 meetings happening concurrently, it’s hard, if not impossible to follow everything and I spent my week running from one room to the next.

views::enumerate in C++23?

I spent an ungodly amount of time over the past couple of years exploring ways to get

views::enumerate (a view that yields an index + an element for each element of a range) to produce a struct with named members (index & value), as this is more ergonomic and safer than std::get<0>(*it). Alas, despite my best efforts and hundreds of hours invested, this proved almost unworkable. In particular, I wanted to avoid that struct (let’s call it enumerate_result) to be viral. The standard does not need another half-baked implementation of std::pair.

My favorite design was for the reference type to be enumerate_result and the value type to be tuple, so that, for example, ranges::to<vector>(some_enumerate_view) would produce a range of tuples rather than a view of enumerate_result.

Alas, I thought this could work, but it really can’t, or at least, it would be extremely complicated and inefficient.

So, I explored a design where both the value and reference types are enumerate_result, but this is also ridiculously complicated, both in terms of specification and implementation. And because of that, I wasn’t confident that I got it right, despite tons of help. And, as we expect most people would use structured bindings anyway, the cost/benefit of going in that direction made less and less sense.

That’s how std::enumerate missed the design deadline for C++23.

Fortunately, thanks to the magic of NB comments, we were able to talk about enumerate in Kona.

I had made sure to have both options (tuple, and aggregate) fully worded, but the deal was simple: we could either get enumerate into C++23 with a tuple as value and reference type… or not at all. The aggregate design simply carried too much risk, for marginal benefits, to the extent I’m not convinced that we could get it correct for 26, and even if we could, I was not sure it provided the right ergonomic trade-offs.

WG21 agreed with me, both that using std::tuple was the sane design direction and that enumerate is valuable enough that getting it into 23 would be useful enough that we should do it at this late stage.

And so, std::enumerate is now targeting C++23 subject to another round of electronic polling (so it’s not yet certain).

Sometimes, perfect is the enemy of good.

The time spent on this was not entirely lost. It was a great learning experience, and we got convertibility between different tuple-like types in the standard (P2165), which is great! std::pair is dead, long live std::tuple.

Unicode

SG16, the Unicode group did not meet, but through in-person conversations, we are starting to make strides in an area of importance to me: the way we reference Unicode and its terminology in the standard. Currently, we refer to ISO10646, an ISO document that is a stripped-down, not synchronized fork of the Unicode Standard with confusing terminology, whose only purpose is to please lawyers. Hopefully, we can simply refer to the primary standard to simplify the spec and to make its understanding easier. Overall, we made good strides in improving support of Unicode in the core language for C++23 and we are not done yet!

A plan is also forming to get some Unicode algorithms in C++23. Stay tuned!

The Future of C++: Safety?

We Held a session on the future of C++.

While some of us hoped to touch on the organizational deficiencies the committee and the community are suffering from, influenced by two presentations at the start, the discussions focused on safety.

One of these presentations was a short form of this excellent CppNow talk.

In the following couple of hours, we said “safety” a lot. It was reminiscent of Prague where, 3 years before, we said “ABI” a lot.

One of the concerns is that C and C++ are being discouraged for new projects by several branches of the US government, which makes memory safety important to address.

No suggestion was offered. Because this is an incredibly difficult problem to solve. For one, are we concerned about safety of new code, or of existing code? (billions of lines of C++ are executed constantly, statistically, that’s a huge amount of CVEs already in production!).

There is no solution, but maybe there are a plethora of targeted solutions to fix some of the common vulnerability vectors. I don’t think C++ will ever be Safe™, but it can be safer. The goal is to reduce the number of CVEs and the cost of fixing them. Safety is a gradient and most vulnerabilities are found in constructs that look more like mediocre C than good modern C++. So the tool to write safe code mostly exists. At the same time, we can’t tell people to write better code or to follow 300 un-toolable guidelines to get a shot at reducing vulnerabilities. There is no such thing as passive safety. Most developers are not experts, experts have bad days or temporarily lose focus.

Safety will likely come in the form of both language solutions, static analysis tools, and runtime tools. But nothing is free. Safety will ultimately crash against other “primary goals” of C++ such as backward compatibility and performance. Who knows what will happen there? We should note that C++ is bad at backward compatibility as we usually break just enough existing code to make migrating to newer standards annoying for large teams, and we only care about performance if it doesn’t affect backward compatibility. So it’s all tradeoffs and it will be interesting to see how safety factors into that inconsistent balancing act over the next few years.

A couple of specific solutions have been brushed on.

Starting by address sanitizers. Arguably the most pragmatic approach to safety. Recompile your code, and you are good to go. Except ASan is slow, sometimes over 2x perf hit. And it was pointed out that running with ASan can actually expose vulnerabilities rather than prevent them (ASan is not designed to run in production), so we should not encourage its use in production builds (but please use it liberally during development).

We can however make address sanitizers MUCH faster (fast enough that enabling them in production on safety critical components makes sense). Such performance requires hardware support to allow ~0 cost pointer tagging. Both recent Intel and ARM chips have added the necessary instructions, and android devices use them as part of the defense mechanisms in low-level critical system components. AMD’s zen 4 similarly supports Upper Address Ignore, so it would seem hardware support for ASan is generally available on recent iterations of common architectures. Note that as far as I can tell, AMD’s version of that feature is not supported by the linux Kernel.

Either way, this is a concrete solution: We need to invest in address sanitizers and hardware support for them.

The other promising solution is static analysis to track the lifetimes of objects during compilation, in IDEs and tools. See The LLVM discourse and This video for what such a tool looks like.

This is exactly like Rust borrow checker, if the borrow checker was blind (because code is hidden in other translation units or later in the file is invisible to the compiler) and drunk (the borrow checker relies on the fact there can be no more than one mutable reference to a given object), but it’s a start.

Until we are willing to change C++ to the point it is no longer recognizable as C++, memory safety cannot be guaranteed.

We will have to see if more concrete things materialize and if any of them can gain some consensus.

During the meeting, we decided to extend the lifetime of temporaries ranges in the range for loop, which is one way to improve safety. Shortly after, JF Bastien proposed to do something about uninitialized variables.

Wherein I propose that C++ initialize all stack variables to zero, preventing ~10% of CVEs.

— JF Bastien (@jfbastien) November 15, 2022

Cost: none.

🔗 https://t.co/LJsDiRl7ZR 🔗 pic.twitter.com/M0dhOkIvOm

I see that as a sort of litmus test in the coal mine. So far, this has engendered hundreds of comments, so there is interest. I think we are a long way from any kind of consensus, but the ball is rolling. It will be interesting to follow.

Overall, I’m not sure we achieved more in that meeting than the recognition that safety is a problem. I guess it’s a necessary first step. And I’m pretty sure that there are strong disagreements about what safety is. For example, people care about termination safety (ie the idea that a program should never terminate even when it ends up in a broken state), which seems antithetical to the notion of safety.

So we are not sure what safety is, or how to get more of that, but we want more of it. Hooray.

But… Most importantly, that “future of C++ session” did not, in fact, talk about the future of C++. Safety, for example, is laudable but it’s a complex topic that will require a lot of research and investments.

And something that has become very apparent to me is that investment in C++ toolchains is suffering along with everything else, certainly more so.

And while CVEs are a huge strain on the industry as a whole, someone is going to have to invest in solutions. As it stands though… The C++ committee, its members, implementers, and maybe the C++ community as large seem to be spread rather thinly. Safety is only one of the many long-standing issues this language faces. How are we going to do all of this? It would also be detrimental to focus on a single problem (to which we have no clear solution) at the detriment of the many other axes that would benefit from improvements (and for which proposals often exist).

It certainly doesn’t help that the committee is hard to get into, and it has gotten harder to get into this past year. One of the many issues here is ISO, an organization that prides itself on amorality and whose benefits to C++ and its users are, I think, questionable at best. Some of the challenges faced by C++ require swift solutions and WG21 is hardly swift. If safety-related work happens and trickles down to users in a decade or so, will our users still be there waiting? There is a sense of urgency but no mechanism to react urgently.

As C++ evolves and gains features, we increase the surface area of things needing maintenance. We can’t release half-baked features like concepts, variadic parameters, ranges, etc, make a keynote about it and move on to the next big thing, so overall the workload increases over time, and our resources are in fact diluted.

As the pandemic struck, many were happy to pause the work entirely until we could get back to business as usual. C++23 is still a great release thanks to the dedication of many people though!

We also did not talk about the successor elephants in the room. I think it’s fair to say many people are dismissive of Carbon, Circle, Val (and even Rust at times), but whether these projects succeed is, to me less important than the question of why all these groups of people decided to start from scratch than to put up with the C++ committee. I don’t believe these projects can be ignored. At the very least they further dilute the pile of talents the C++ community, the committee, and implementers can draw from.

Following that meeting, we were asked whether we are optimistic about the future of C++. Maybe I’m biased in that I’ve always been bad at this optimism thing but… are you?

Customization Function Objects.

The excellent Lewis Baker Presented P2547R1 (Language Support for Customisable Functions) to Evolution.

I don’t think it went particularly great.

P2547 was born from taking the requirements of sender/receivers (currently based on tag_invoke), and that of other customization mechanisms in the standard library (of which there are many), and designing something that supports these use cases while reusing as much of the existing features of the language as possible.

As such a CFO is just a regular object, which when called has slightly tweaked lookup rules to find the right implementation of the customization function in the appropriate namespace, and support a default implementation. Because there are 2 declarations (that of the CFO and that of the actual customization), we also need to tweak the resolution of constraints and no except specifications. Because there is a need for sender receivers to be able to forward calls through executors and senders we needed a way to specify these forwarding functions. The last complexity comes from the need to support explicit template parameters in calls such as std::get<N> and std::get<T> (which are 2 different overload sets despite having the same name).

Yet our solution is deemed too complex, so I guess we need to go back to the drawing board.

It is not clear to me if the criticism is about the solution or the requirements though.

See, the C++ committee is divided into these groups, like “Language Evolution” and “Library Evolution” so when we try to solve a problem that the library folks have, well, the library folks aren’t in the room. And we end up having to palliate core language deficiencies with library solutions which are always, by their very nature, clunky and inefficient.

It’s a pervasive organizational and cultural problem. Library folks are not usually hopeful that the language will solve their needs and will devise the craziest hacks to get what they need, becoming desensitized to the craziness of their workarounds over time, to the detriment of end users.

I don’t know if the language folks understand how bad this problem truly is for people writing and using libraries.

We need more vertical integration!

I remember Titus Winters once said, “If the librarians of your language are starting to

recommend that we stop writing functions, that should be a warning sign”. One of the issues here is ADL and CFO shield users from ADL. The problem is exacerbated by the fact each new library component introduces a different approach to solving that problem, and tag_invoke is but the last iteration in that design space.

The good news is that yes, the language folks do agree there is a problem that needs solving and wants to see a different solution.

What would a solution look like, we have no idea.

We want ponies.

Maybe one that looks more like Rust generics, even if generics do not solve the forwarding use cases on which std::execution built its castle.

In the meantime, Sean Baxter has been experimenting with features in the design space of C++0x Concepts, rust traits, and generic type erasure.

I hope something comes to fruition. But something needs to happen soon if we are to save our users and our compilers from tag_invoke and its one giant overload set.

The best part is, no one is paid to work on this!

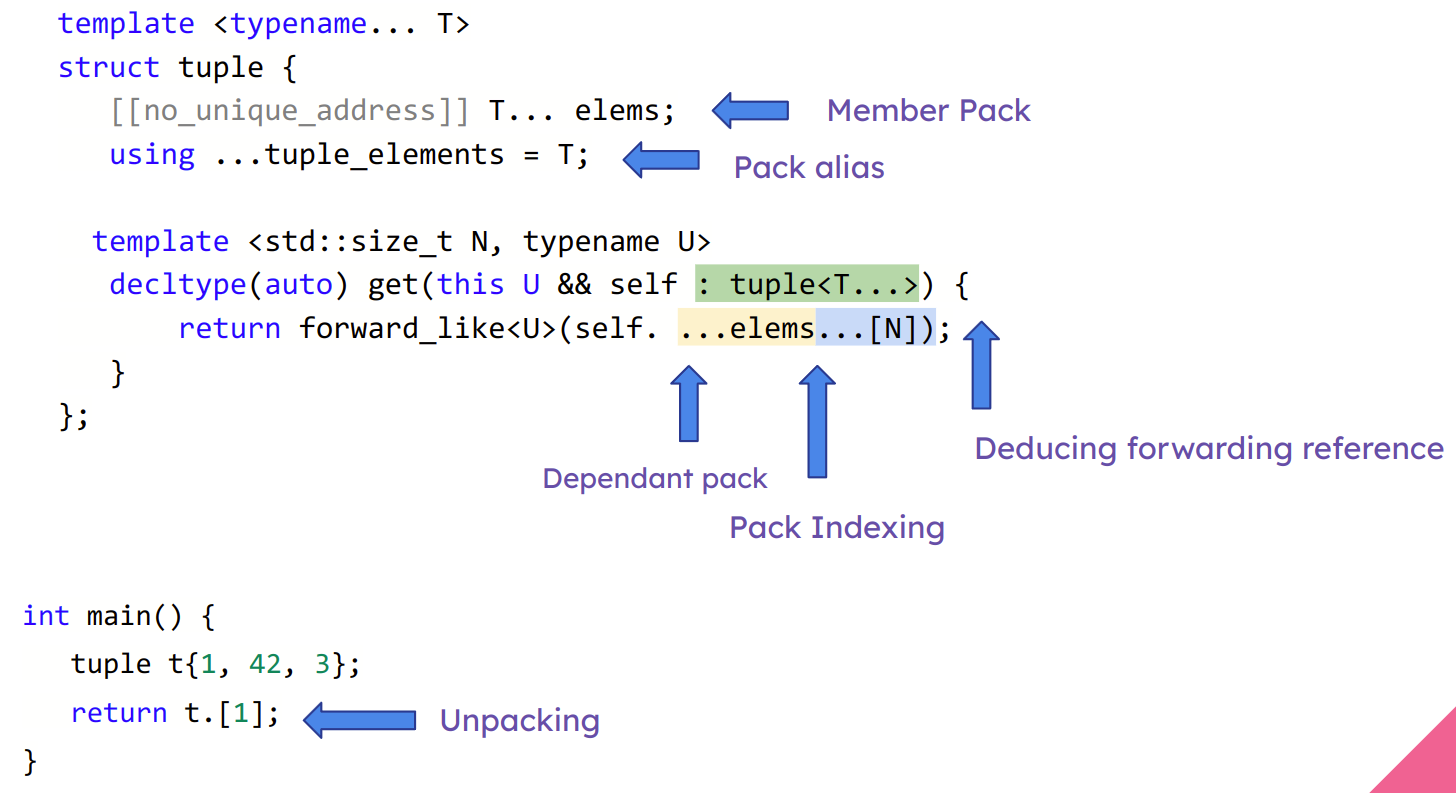

Indexing a pack by Committee

The most important thing for me that week was to present P2632. A plan for better template meta programming facilities in C++26. It is, after all, the reason a 24h hour journey seemed justified. The idea of this paper was, in no small part to take some good ideas from Circle which are known to improve maintainability and productivity and standardize them, being careful to strike for a reasonably minimal subset and to reimplement everything in Clang so that we can derive a specification with confidence and gain more experience with it all. The set of features proposed either made currently impossible-to-write code possible (universal template parameters) or greatly reduced the complexity of already used techniques (improving pack manipulation greatly reduces code complexity).

It also draws a lot from preexisting work over the past decade. And it extends the languages in mostly obvious ways, in many cases. It’s about plugging holes, not inventing a brand-new paradigm. We don’t need new paradigms!

In particular, I expected pack indexing to be a trivial sale. I even had a paper, complete with wording and 2 implementations. The only thing missing was girl scouts cookies.

The way I see it, packs are sequences and indexing is a basis operation of sequences. Done deal, right? (Inevitably there would have been bikeshedding discussions but there aren’t many logical choices here.)

Boy was I wrong. The reception to that paper was a lot colder than I expected. WG21, even after a few years, is rather unpredictable.

One argument that I was not expecting is that… users don’t write templates and do metaprogramming even less so. It is an interesting position, as generic programming is to me one of the cornerstones of C++. Template Meta Programming is the entire reason Stepanov concluded that C++ was the only language that could support his revolutionary library, which we now know as the STL. And as types became more complex, we needed more tools to manipulate them. Variadic template parameters in C++11 simplified a lot of code and allowed the implementation of variant, tuple, etc. Further refinements, like fold expressions, were also successful additions addressing real problems.

How many people write libraries relying on these features is hard to quantify. Certainly a rather small subset of our user base, that’s true. Still a few thousand people, at least. And how many users do these people serve? The entire community!

See, making the standard types faster to compile, making boost, CTRE, FMT, Qt, libunifex, the various JSON libraries which are heavily using template metaprogramming and the list goes on and on, benefits everyone (it’s not just compile times, but also better error messages, easier maintenance and therefore fewer opportunities for bugs) that would benefit…

The dichotomy between “library writers” and “application writers” is also very C++ specific and artificial. The reason few people write library code, or generic code, or implement strong types, is that it is very hard to do. If it was much easier to express, more would do it. There is a safety argument to that: strong type safety reduces the risk of vulnerabilities and so we should encourage these techniques by making them more accessible.

Don’t worry though, reflection will solve everything. At least, that was another argument against improving metaprogramming. This one, I expected.

And it is true. If you can reflect on a pack (which needs syntax), you can write a function that takes a vector of meta info (which needs library support), returns the first one, and reifies it (which needs syntax). You might, I was told, avoid the vector entirely somehow, so maybe the compiler would not die in the process, but it would require yet more syntax and if you can do that for reflection, why not allow indexing of packs in the first place?

Because… it would require syntax and add complexity to the language!

sizeof…(pack) also uses syntax and that has not been challenging to users, despite the interesting reuse of the sizeof keyword.

Don’t get me wrong, I fully support reflection (although I will say that we have not made progress in the past few years), but using reflection to index a pack is like trying to kill a fly with a nuclear warhead. For pack slicing (getting a subset of a pack), the case for reflection is a little more nuanced - the language should not support arbitrary slicing; we have algorithms for that, but in practice, most slicing operations are excluding either the first or last elements. The way I see it, the language should make simple things simple, and everything else possible.

Given a C++ parameter pack `P`, how to you get the `n`th type in it? Rules: short as possible, no additional definitions. I'm sure we can do better than `std::remove_reference_t<decltype(std::get<n>(*static_cast<std::tuple<P...>*>(nullptr)))>`?

— 🇺🇦 Andrei Alexandrescu 🇺🇦 (@incomputable) November 10, 2022

Another argument was that template meta-programming is terrible actually, which I find hilarious given that TMP is often a reason cited by people not to jump to rust. And we could make it better.

Finally, we should just be able to convert packs to some kind of objects that we can iterate. I could not completely follow that discussion, having to be in multiple rooms at once, but I do have one question: what is the type of a pack of template template parameters? Packs are fundamentally heterogeneous beasts and with luck, they may even contain heterogeneous kinds of entities in the future.

Given that our time is, in fact, limited, maybe introducing new kinds of objects/expressions in the language isn’t something we should entertain given that the few operations that are actually useful and packs and for which reflection is overkill are actually few.

C++ variadic templates seem to be the result of a gang war. One faction wanted to make them as complicated as possible. Another wanted to give variadics as little power as possible. Those gangs canceled each other out and the design was done by a group of TeX macro experts.

— 🇺🇦 Andrei Alexandrescu 🇺🇦 (@incomputable) October 11, 2022

Tuple unpacking is also a bit stuck because of the implementation complexity for one vendor, so we might burden users with syntactic ornaments that other implementations could maybe not require. If we even want tuple unpacking? The issue with the fact my paper presented a vision is that I’m not sure which parts of it people had cold or warm reactions to.

In particular, forwarding reference deduction and universal template parameters are not things reflection or even code injection could ever solve.

Anyway, I’ll keep trying. The beauty of WG21 is that you’d be a fool to do the same thing twice and expect the same result.

Random bits

static_vector, SBO vectors

The discussions about new vector-like containers were interesting. Namely, what happens when pushing to a full static_vector?

I’m strongly in the camp that it should be a precondition violation (UB, bonus point for terminating), while others prefer an exception.

But, are there scenarios when you can throw but not allocate? and if you can allocate, maybe you wanted an SBO vector instead!

A compromise might be to have try_push/try_emplace methods on all containers.

#embed

int main() {

const unsigned char foo[] = {

#embed "foo.bin"

};

}

#embed is heading to C++26. I’m annoyed that we ended up with a preprocessor solution that spews integer tokens unless the implementation does some clever optimization, but… It does the job and we missed enough opportunities for some better solutions. There is also no reason to deviate from C. This is not an area where purity of design would justify investing more resources into research! Ship it!

A nice placeholder with no name

Naming is hard, and not everything needs a name. We decided we like P2169.

We should be able to use _ as the name of variables whose name

really doesn’t matter, as well as in pattern matching patterns.

void f() {

int _ = 0;

_++; // ok

auto [_, foo] = some_destructurable();

_++; // ill-formed, multiple _ in the same scope

}

Library fundamentals no more!

We decided to publish the library fundamentals V3, which contains a bunch of things the committee neither wanted to standardize nor kill. But, more importantly, we decided not to pursue these kind of general-purpose grab-all library TSes in the future. Library fundamental TS v3 is therefore the last of its name. In the future, proposals should all be iterated as paper until LEWG is happy with them, or decide not to pursue them. This is excellent news as doing TSes aimlessly strains limited resources and has not, historically, led to a better outcome.

What’s next?

The next meeting is in Issaquah (near Seatle) in February, and I plan to be there. I’m not particularly looking forward to the weather, but it will be the very last meeting of C++23. All the remaining NB comments will be resolved and C++ will be done!

Well… until C++26 at least.

I plan to keep working on Template Meta Programming, Unicode, ranges, and small improvements, and trying to balance that with Clang maintenance. Time flies.

The committee as a whole is certainly going to focus on asynchronous and heterogeneous programming. Reflection, Pattern Matching, and SIMD are also areas that might make significant progress.

Going forward, the plan or the hope at least is to continue meeting both remotely and in person. We certainly need to do both to keep up with the workload!

A hui hou kākou.

Share on