December 11, 2022

If we must, let's talk about safety

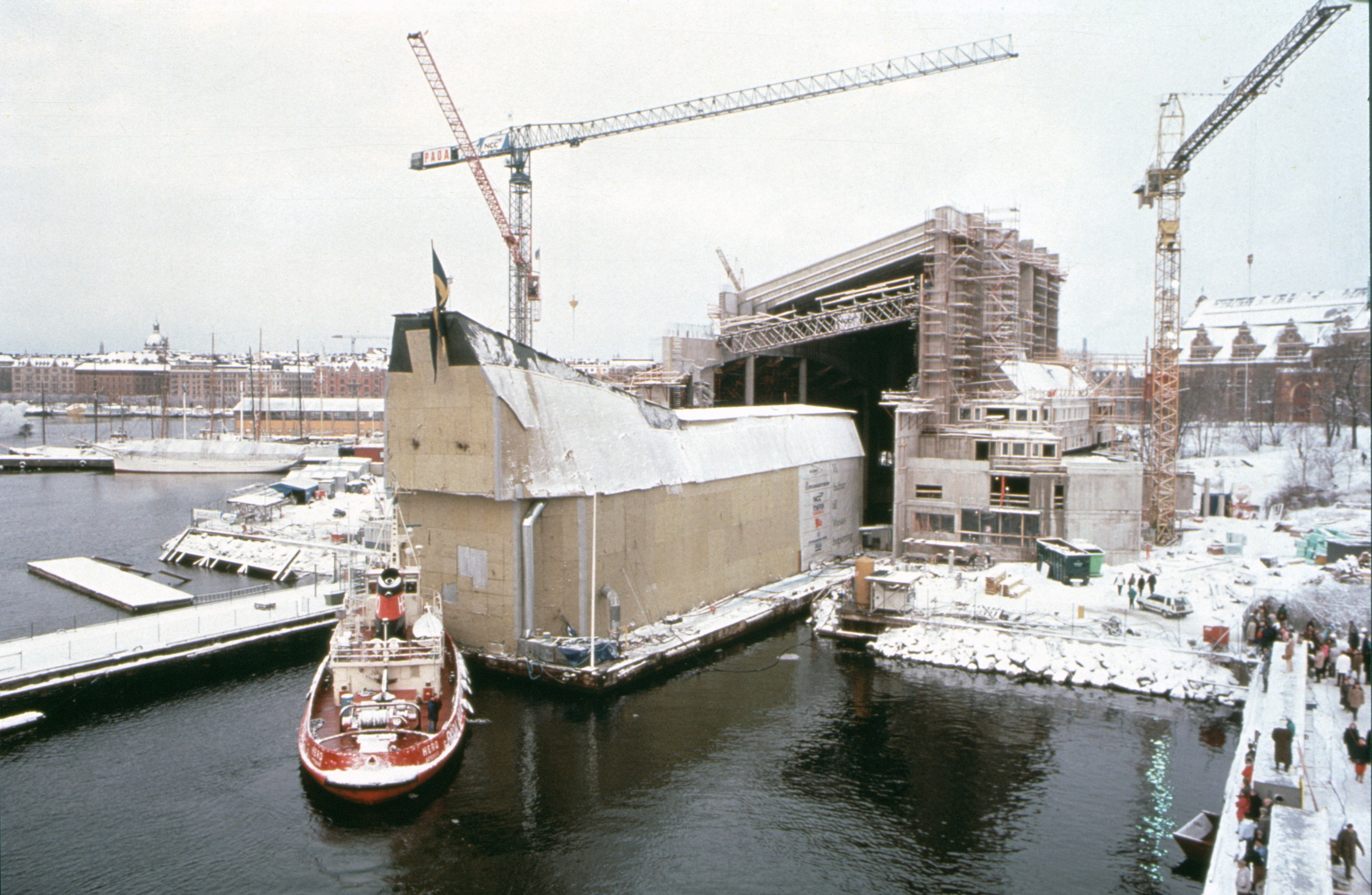

How would you put a 69 meters long, 50 meters tall, 1210 tonnes ship in a museum? A boat so large and so great it sank 100 meters into her maiden voyage?

Well, you can’t. Entombed in concrete, the Vasa will never sail again

But, if you really wanted to build a monument to hubris, unsound engineering requirements, and design by kingship,

you could design and build a museum around the Vasa.

A cakewalk and eating it too

So what if instead, you wanted to put a correct-by-construction, reliable and ergonomic lifetime analysis mechanism in a programming language?

Through academic research, careful consideration of previous works, and tinkering you would realize that either:

-

You need to be able to reason globally about the lifetime of each reference and pointer through assignments, function calls, and translation units. And that, for any non-trivial program, doing so may be either impossible or impractical.

-

You need to invent new computer science contradicting existing computer science.

-

You can ban aliasing from your programming language, and that would be enough for the compiler to be able to reason locally about the lifetime of objects. This is a bit restrictive though, so maybe you could allow an arbitrary number of immutable references to a variable, or a single mutable reference. Or, you simply don’t have references, everything is a copy. Either way, everything has a well-defined owner, and, at any single point in time, at most one entity can mutate any one object. This is great, you marvel at your creation. You realize that this simple idea not only gives you memory safety but also thread safety. And better tools too. Cherry on top, the generated code is faster too. You finally created a language competitive with Fortran, how great is that? You may even go the extra mile and prove this is all mathematically sound.

Alas, I’m afraid, dear reader, that this is indeed a C++ blog post.

Mathematics won’t save you now.

And so we must contend with the gloomy reality that is backward compatibility. Or rather, existing code.

Of all the C++ code written these past 40 years, a fair amount probably still runs. And the Vasa is no ship of Theseus. It would be, to my dismay, naive to imagine that all of that production code qualifies as modern C++. We should be so lucky to find reasonable C++ in consequential proportions. So, we should not expect guidelines about lifetimes and ownership to be followed.

It gets worse: we also find a lot of C code. There is no boundary between the two languages, from an ownership standpoint. It’s all the same happy jumbled mass of messy stumbling heap.

Not even a sprinkling of unsafe keywords to keep us vigilantly on our toes.

After all, there is no point in putting a warning sign in the very middle of a vast landmine field.

I like to think that most vulnerabilities in C++ have already been written.

New code is more likely to abide by modern practices and use language and library facilities that make it easier to write correct code. Maybe. I am trying to be optimistic.

Safety by good practices and convention certainly is no guarantee of anything but it does help, to a point.

Good abstractions, good interfaces, good types. All of that leads to safer code.

But the point I’m trying to make here is that to improve safety in C++ at the language level, we need to somehow consider all that existing C and C++ code. We cannot just ask people to write excellent and perfect code at all times. People are not machines (and you should see the kind of code machines write…)! Often, we can’t even convince people to update their toolchains. Most of all, we can’t ask people to abandon all their code.

By Rust’s definition, all of C++ is unsafe. Well, not all: functions dealing only in values are fine.

But then again no, values can be non-owning pointers in disguise! Oh span, span, delicious span.

We can’t even make any statement about constexpr functions: if constant evaluations are indeed safe, constexpr is just an ornament we put everywhere to celebrate Xmas.

Borrowing the borrow checker

We can imagine adding non-aliasing references to C++. I am not sure exactly how. But it would go swimmingly though, exactly as it went with rvalue references. We also would have to figure out destructive move. We failed to do that once, but why should that stop anyone? So armed with our imaginary tools, we can start to have a nice and cozy “island of safety”. Our new safe code can call other safe code.

Surrounded by an army of raw pointer zombies, every time we would call or be called by the “unsafe subset of C++” (which would be 99.999% of C++ at that point), we risk the walls around our little safe haven to be toppled over.

See, there is relatively little unsafe code in Rust and a lot of care has to be put to ensure that this code is, in fact, safe. It’s manageable because it is limited, clearly delimited, and contained in space. Keeping a zombie in the basement is a tolerable risk, living encircled by zombies very much less so.

Rust is not about having no dragons, it’s about containing them.

unsafe also raises red flags in code reviews, which is exactly what we want.

So even if we could add a borrow checker to C++, would there be even a point? C++, is a “continent of unsafety”; by having a safe C++-ish language in C++, that dialect would look a bit foreign to most C++ devs, and it would integrate poorly, by design. We would need a clear boundary. And the safe dialect would have different capabilities, could not reuse existing libraries (or even the standard library), and so forth. And then we’d try to make it generic, which would be a good way to stretch our zombie metaphor for a few more seasons.

Sure, there are self-contained components that require more safety than others. For example, an authentication component, and a cryptography library.

We could use our safe dialect to write these.

And, because we are doing that to decrease the risk of vulnerabilities, we would reduce the surface area of the boundary between that new safe, green field component and the rest of the code as much as possible.

We end up with a piece of code that does not look like the rest of our C++ nor integrate with it. At this point, could we have not written that piece of code in… Rust?

The rules of interaction between a hypothetical safe C++ and C++ would be no different than that of C++ and Rust through a foreign function interface.

“Rewrite it in a slightly different yet completely incompatible C++!” sure is a rallying cry!

But we care about safety, right?

Ultimately, for many reasons, the idea that we can add safety into the language is a bit ridiculous to me. Besides the large amount of existing code that needs a solution, we also would like a solution sometime this century. And we do not have a good track record of doing things swiftly.

I find it a bit terrifying how the committee is sometimes willing to push things by 3 years, with little thought about how users would be impacted.

If you look at concepts, coroutines, pattern matching, modules, and other medium-sized work, you are looking at a decade on average to standardize a watered down minimal viable proposal.

However you look at it, shoving “safety” in the language sounds more complex than all of these things.

Alas WG21 rarely reflects on its own abilities, nor is it willing to question its processes, so I’m sure some people will be keen to try. And I wish them all the luck.

After all, we need to do something right?

Well, yes.

Fortunately, there are solutions.

If safety by construction is not realistically attainable, maybe we can at least put a safety net over the bottomless pit of vulnerabilities that we have to contend with.

And I think we can. If we can’t do it at compile time, let’s do it at runtime. And sure, keeping up with the philosophy of catching bugs as early as possible, doing it at runtime is awfully late. On the other hand, if we can do some of that by just recompiling existing code, without modifying any of it… that may be realistic? I’m sure some people have code they don’t have the source for they want to keep running but… yeah that code needs to be sandboxed, cast in a block of concrete and sealed in a lead-lined room with armed guards - and even then I have my doubts. So let’s assume that we can at least recompile our code.

Sufficiently advanced hardware could run a form of address sanitizer in the CPU. Recent Android phones can already do that! That system is such that, if you access memory that belongs to another object, you get a runtime error.

Am I suggesting that the solution to safety is to deploy new hardware? Yes, Yes I am. And as long as the timescale may be, I think there is a clear path to that technology - if only because it’s already being done, and it’s likely other vendors are looking at doing it too. Changing hardware regularly is something the industry has to do anyway, whereas doing large rewrites carries risks.

So, we can imagine getting to a point where most memory access errors would crash during testing, as well as in production, and we would be free from most (not all, there are false negatives) memory-related vulnerabilities.

And yes, that’s not elegant, it’s not very Rust-like.

But I think it happens to be pragmatic and doable, unlike about anything else that has been proposed or dreamed of. It may not work for everyone but it’s a tool that the industry can give people; it’s at least one answer. We do not have the luxury of elegance, at least not in the short or mid-term.

Dogma

Okay but there are a few issues with that idea: First, I’m suggesting crashing in production, and two, runtime checks, even at the hardware level, surely will impact performance. Won’t somebody think about the CPU cycles?

I think this is where things usually tend to become a bit emotional.

Let’s start with performance. Let’s talk about that. Which is a pointless conversation to have because I don’t have any benchmarks. But, for the philosophical exercise, what would it cost to run some form of “Trap on incorrect memory access” in production? If we did it with Valgrind, we may be looking at a 100x slowdown, which is not acceptable. Address sanitizer advertises a 2x slowdown. Much better, but way too slow for anyone to run with it in production. Not bad for testing though.

Something like ARM MTE advertises a 1%-5% slowdown, and a 5% or so increase in memory usage. (Note that this is at some point trading accuracy for performance, and some incorrect access may go undetected by ARM’s MTE, there is no free lunch, sorry.)

Now, we can have a conversation: Is a 1-5% overhead justifiable in the name of increased memory safety?

As an industry, when it was found out that programs can spy on the internal state of CPUs and recover sensitive information, bypassing all forms of VMs isolations and kernel protection, we quickly deployed mitigations, sparing no expense. In fact, in the worst cases, Meltdown mitigations could cost 20% of CPU performance. Fine. It’s not like we had a choice, did we? Process isolation is the only thing between us and complete anarchy. Of course, that was annoying, and through improved CPUs architectures, compilers, and kernels heroics smart folks got that cost down to 0-5%.

But if we were able to eat 20% of our compute and survive, maybe a few percent perf hit to mitigate 70% of vulnerabilities isn’t a bad deal, is it?

Alas, I think there is a bit of overconfidence there. See, doing anything at runtime in the name of safety is wasteful if the code is correct. Hahahaha.

In fact, it’s not possible to talk about safety in C++ without talking about performance. It’s not like C++ always cares about performance, mind you. We are more than happy to lose performance in the name of ABI, or in the name of strong exceptions guarantees for exceptions that can never be thrown, or by still not having figured out relocation after 20 years.

But wasting cycles on the off-chance that someone blows their feet? Just don’t blow your feet, mate. C++ is all about performance, damn be your toes.

So the question of the price we are willing to pay for safety is an important point. In other professions, I doubt engineers would be too keen to argue against safety margins. Journalists tend to make a big fuss when bridges collapse.

Maybe the winds are shifting. I mean, they definitely are.

Users, Governments, and Industries want safety.

In part, because they see it’s possible, and in part because they had this great idea to link your toaster to your bank account, so now they kind of need safety, preferably 10 years ago. It’s costing serious money. Maybe, we can hold the cynical view that these talks of safety are just trendy, or a phase, or something, and it’s all hot air. Even if it was, which I really don’t think it is, people are going to use tools they enjoy using, not meeting the wants of users is not a recipe for success.

And then maybe that question about the affordability of safety reduces to “Do we buy more hardware or do we rewrite it in Rust?”. I hope we give the people who can’t rewrite it in Rust options. Soon. Rewrites ain’t cheap.

Okay so for the sake of the argument, let’s say that we are all convinced we need to check memory accesses at runtime, at least until the unicorns shine down on us.

Now what?

Down with Safety!

We are almost 2500 words into this fulmination, and I have a confession to make. I hate this word. Safety. I hate this word. I really do. What does it mean? Seriously? “Safety” is hyper-focusing on the wrong thing and we are hyper-focusing on it.

Under the right circumstances, any bug can be exploited, and lead to vulnerabilities. On the contrary, a correct system (both per the specification and the developer’s intent), is less likely to have vectors of attacks.

The only difference between an exploitable bug and one which isn’t is who is holding the foot gun.

Of course, things tend to only be correct in some domains so you can always poke at things with adversarial inputs, but can a system that let unsanitized input slip in ever be correct by any stretch of the imagination? More generally, most logic bugs can’t be caught by the language or the tools, our jobs won’t be automated away just yet.

I think this is a better way to frame the discussion: How do we deal with code known to be incorrect?

A program that, for example, tries to access out-of-bound memory is incorrect and out-of-line. An interesting property of incorrect programs is that we never know why they are incorrect when they start to act unexpectedly. If the program was expecting to be in that specific state, it would be correct. Bugs are unknowns and failure of expectations. The program found itself in a state that was unaccounted for and its behavior is now… undefined.

You knew we would get there, didn’t you?

Before we continue, we should explain “Undefined Behavior”.

It’s just… behavior that is not defined. In other words, behavior that does not make sense. An optimizer, which inlines, reorders, unloops, removes, factorizes, vectorizes, etc code, needs to ensure all of these transformations preserve semantics throughout. And the only way it can do that is to assume at the start that the program makes sense. One cannot preserve the semantics of something which does not make sense.

So it’s not like the big bad implementer is actively trying to enlarge the holes you made in your metatarsals, instead, the compiler just assumes (because it has no other choice), that you wrote something sensible. If that assumption is wrong, the optimizer will possibly make it worse, by no fault of its own. Garbage in, garbage out. This is why we say that UB can time travel, or do anything including summoning nasal demons. Maybe it’s not a super helpful characterization, but what it’s trying to express is that it’s not possible to reason, or predict. the behavior of a program that is not correct. And yes, through optimizations UB can affect code preceding it. Spooky indeed.

There is no denying that UB is a very sharp knife and ideally we’d like less or none of it. Let’s remove it all! To remove undefined behavior is to define behavior. Let’s say you access uninitialized memory, should we just…pretend that this memory is not garbage? What about all the invariants some type now imposes on your garbage memory? What about integer division by 0? Should we make up new math?

And yeah, not all UB is always reasonable, I’ll gladly concede that. Sometimes, UB is added out of laziness, to gain consensus, or for failure to realize how dangerous it is. But a lot of times, people simply would rather not give meaning to which has none, for there lies madness.

And so, if our CPU is nice enough and lucky enough to trap incorrect memory access, it should crash.

Note that your program will already crash in that scenario.

But only if your request is so ludicrous it happens to correspond to an unloaded page.

Imagine ptr points to an array of 1 element.

Maybe *(ptr + 43) crashes, but *(ptr + 42) points to garbage memory.

Is the former worse than the latter? One should hope not.

Of course, in both cases it’s UB but at least a crash is predictable and more easily fixable.

You just can’t go around killing people.

Yet, there is this idea that crashing is bad. And yes, it is. But consider the alternative: letting a program that got itself in an incorrect state, who knows how, run. The hope is that well, it’s maybe not as bad as one might think, and maybe the program will limp long enough to do something good. Which in fairness it might. It might also do something bad. Like going off on a murderous rampage.

There is no way to tell sadly. And yes, I’m being a tad hyperbolic but the arguments against termination are also too often alarmist.

- “What if a pacemaker terminates? That would be bad!!” Are you telling me that you got some C++ in a medical device, with no redundancy whatsoever and the thing would overflow, or access out-of-bound memory? But what if the chip inside the pacemaker doesn’t terminate, and instead does its thing slightly out of beat, sending the patient into arrhythmia, and killing them in the process?

- “What if an application at the heart of the banking system overflows and crashes, and…” Well, what if it doesn’t crash? Are you really letting a transaction overflow?

I should be a bit nuanced here. We can find dramatic examples both ways. The inaugural Ariane 5 flight was probably doomed because of trapping overflow. Who knows what would have happened if it wrapped instead? Maybe the thing would have gone on its merry way or crashed a few seconds later.

The Linux Kernel has a policy that nothing can violently terminate because being the kernel, there would not be any opportunity to report the error otherwise. Fair enough. but you also open yourself to attack vectors. Or loss of data, or whatever else can happen when a kernel goes rabid.

I’m sure there are unknown unknowns that cause the Linux Kernel crashes anyway (but this being an article about C++, the Linux kernel is forever off-topic).

If the system is critical enough, having redundancies a level down is the only realistic way to ensure it keeps running. Let the thing crash, reboot it. Of course, these fail-safe systems are hard to test and may also cause problems. UB all the way down! Rust will probably take the approach of having a set of libraries that are designed to work in a no-panic environment, which some C++ folks would call a dialect and be angry about. But that shows that termination being bad is not the common case and so it needs dedicated considerations and tools that should have no impact on the 99% use case. I guess in such an environment, everything would have to be safe.

Leaving the kernel aside, for integer overflow specifically, Rust takes the approach of panicking in debug, and letting signed overflows wrap in release - it’s still UB in the spec, though, so if you were to rely on it you’d anger the crab gods. It’s UB because it does not make sense. That’s not how math work. If you explain to a kid that if they have 127 candies at Halloween and they get one more candy, they have to give all of their candies away, they might realize too young that grown-ups deserve to sit in the corner forever. Wrapping just transforms a bug into another bug, which then snowballs into a bigger issue, hoping that it will become someone else’s mess to deal with.

John Regehr makes the case that languages do have little choice of following the semantics of what the hardware supports, and trapping semantics for integer overflow would need some help from the hardware folks (neither amd64 nor Arm can trap on overflow) - which in turn would have industry-wide benefits. The reason this hardware does not exist is that Hardware folks 20 years ago thought it wasn’t worth the real estate cost.

Division always panics. I wonder what happens if one divides in the kernel. It’s not exactly safe.

Correct by confusion

Back to C++. In no case should exceptions ever be involved. Ever.

Even if there is a fire.

std::logic_error should not exist. It should be understood as std::wtf_exception. And if someone throws that, what are you going to do? Especially if the exception comes from a third-party library or something deep in the application having an aneurysm. It manages to be, impressively, even less actionable than std::bad_alloc.

But, I get it. Confronted with annoying bugs, instead of fixing them - a difficult and costly endeavor assuredly, why not just… let it happen and try to plug the holes afterward? When I was younger, (and believe it or not, stupider), I wrote some very bad concurrency code, and then some more code trying to hide the fact that my concurrency code was as racy as an F1 car on fire… it’s a race to the bottom.

I did not understand these bugs, I didn’t know anything and I had no tools. Valgrind was still state of the art back then, and I was anything but.

I probably spent more time circumventing bugs than fixing them. Hey, that printf totally removes a crash there. In fact, the best thing that program did was crash.

It would reboot itself, and try to show some stack trace to the end users, and it had tons of logs that were most useful to track down logic errors.

But I think the idea of fixing the symptoms instead of the cause is still alarmingly present. Something is comforting about wide contracts, and nice systems kindly sweeping bugs under the rug. No one wants to deal with panics and crashes. It appears to work, ship it. Just remove that assert, it will be fine.

Alas, this is how you write vulnerable, unstable, unmaintainable programs. UNSAFETY, shouts the crab, smugly.

Clean preconditions, enforced, lead to a more robust design.

The idea is simple: instead of foaming at the mouth and shouting about memory safety, we should look at all checkable UB and precondition violations and assert on them. This is what I hoped for contract, the other C++ feature is highly related to the S-word and going nowhere.

There is absolutely nothing new here.

Some distributions even ship a standard C++ with assertions enabled.

These tools exist and are definitely a piece of the puzzle.

std::span was designed from the start to be bound-checked and that kind of safety has seemingly very little performance impact in Rust.

I’d love to see similar measurements in C++.

Other ideas include banning pointer arithmetics, and even improving diagnostics for lifetime issues. Indeed, we cannot offer the same guarantees as Rust but we can sometimes know at compile time that a piece of code is definitely wrong.

We also need better tools to prevent UB from happening. In its arsenal, Rust offers saturating arithmetic, checked arithmetics (returning Optional), and wrapping arithmetics. I hope some of that comes to C++26.

If you expect overflow to happen, deal with it before it does, not after.

None of that requires changes to the core C++ language though. They are practical solutions that we could have deployed years ago. Luckily, most of these things don’t even need to involve the C++ committee.

And to be clear, there is no one solution to the safety and correctness problems, but a myriad of imperfect and incomplete solutions that, when combined, would get us to a much less scary place.

Neither C++ nor Rust will ever be safe. They don’t need to be. They just need to be safe enough that vulnerabilities are rare, easier to find, and harder to exploit.

Things like hardware ASan, hardware overflow trapping, etc would be useful to Rust as well. A good defense has many layers and relying on any one solution exclusively is not sufficient.

First born unicorn, dream of Carcinization

The Rust borrow checker is just one such tool, one that works because Rust was designed fairly early on around the idea of not having aliasing. And sure it’s something we should marvel at, as it was novel and exciting, or at least novel and exciting outside of academic toys. But novelty fades into the ordinary. Rust developers don’t think about the borrow checker that much, it’s just very natural and mundane for them. After all, why would you not have strong memory safety guarantees in your programming language? Crazy talk!

But maybe the reason discussions about Rust in the C++ community focus solely on memory safety and the borrow checker is because we want a taste of the greener grass. It’s the one thing we can’t have.

We could have everything else. We can have asserting preconditions, we can have runtime bound checking. We can have well-defined or asserting arithmetics. We can have correctness and we can have safety. We don’t.

Rust understands the value of taking the resources to ensure the correctness of running programs. Correctness by default. Safety first. Even without a borrow checker, GCC’s Rust implementation is less sharp of a tool than C++.

They have a strong mental model for strong safety. They don’t throw exceptions in the presence of logic errors, with the naive hope that someone will handle that somehow, somewhere, and that the program should do something, anything to keep running.

And they do care about performance, undoubtedly. In many cases, Rust is as fast or faster than C++. And in very rare cases, the developer does know better than the compiler and there are escape hatches to unhook the safety harness, even if that comes with a lot of safety stickers in the documentation.

How C++ prioritizes its goals going forward will be key.

Justifying the most unergonomic and dangerous designs in the name of performance, not asserting on precondition violations, not bound checking on the assumption that it might hurt performance, silencing known UB, propagating design mistakes in exceptions, etc… is what make C++ a very sharp tool. And sure that’s fast but…is it faster? Is it a good default? Is it justifiably faster? Have we benchmarked?

And yes, because Rust has more robust foundations, it gets safety at a lesser cost than C++ will have to pay.

We’ll need to accept that.

But the borrow checker is not what makes Rust safe. Rust is safe because it decides to put correctness first by default.

Rust is safe by culture.

🦀🦀🦀

Share on