July 7, 2018

Concept and template syntax take 836

The return of the adjective syntax

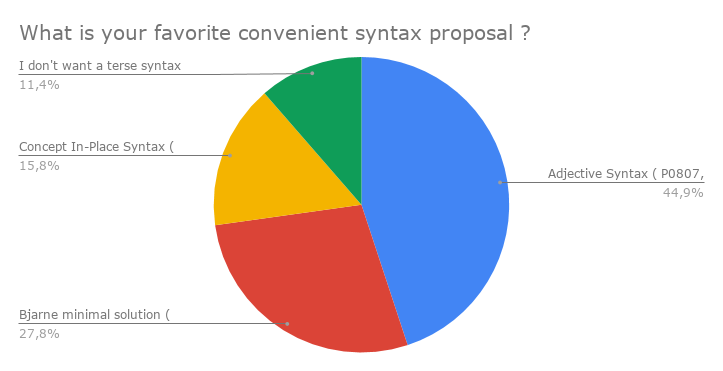

A couple of weeks ago, I made an article on concept terse syntax and I thank the people who took the time to take the poll, it was quite revealing.

And since then a new paper, P1141 - Yet another approach for constrained declarations came out. Despite the name, it’s pretty much the Adjective syntax, repacked with an impressive authors list including Herb Sutter (author of the In-Place syntax proposal), Bjarne Stroustrup and Gabriel Dos Reis (authors of “minimal solution” proposals) and Thomas Köppe (author of one of the adjective syntax proposal), so it would seem that we are converging towards a solution that pleases a large number of people (and that is, after all, the name of the game).

This will please most of my readers.

I don’t want to sound like a broken record, but I think this syntax has a number of advantages including being easy to read, teach, and is unambiguous. It closes a bit of the difference gap between lambda and functions.

This is what is being proposed by that paper

void f(Sortable auto x); /* constrained parameter */

void f(auto x); /* unconstrained parameter */

Sortable auto f(); /* return type */

template <Sortable Container> /*type*/

template <Sortable auto c> /*value*/

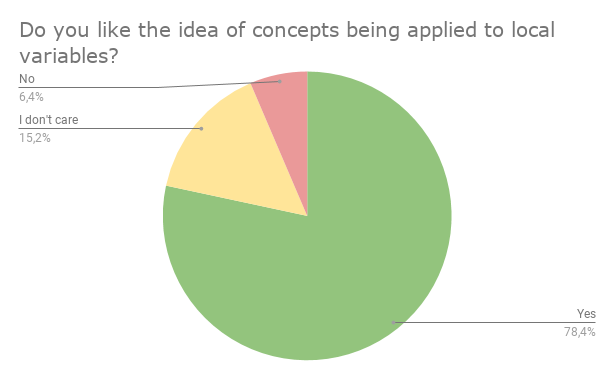

This paper also proposes constrained variables, a feature that seems quite popular.

And so this paper will let you write

Container auto c = buildClientList();

For convenience, it makes auto optional in a few places making the syntax terser.

For variables:

Container c = buildClientList(); //Notice the lack of auto

For return parameter type:

Regular get_object();

auto get_object() -> Regular;

The paper also addresses that ConceptName auto should not be separated by cv-qualifiers which I think is the only reasonable approach to that particular issue.

The constrained type, is a single entity to which cv-qualifiers are then applied, whether on the west or on the east.

Finally, it allows unconstrained deduced function parameters, such that lambda and function is once again identical

[](const auto & foo) {} // Generic lambda

auto f(const auto & foo); // Function template with a single unconstrained parameter

A few issues

I think there are a few sacrifices made, so let us go over some issues and propose some fixes. Importantly, all changes I’m proposing here are additives. Nothing needs to be removed or altered.

Most of the issues have been discussed already, so I am sure they are the fruit of conscious choices to make the proposal lighter.

Constrained non type parameter.

P1141 - Yet another approach for constrained declarations] proposes 2 new syntaxes for template parameters

<Sortable Foo> //A type Foo which satisfies Sortable

<Sortable auto foo> //A value foo whose type satisfies Sortable

Along with existing (plain C++17) syntaxes, this gives us

<typename Foo> // Any type

<auto Foo> // Any value

<int Foo> // A value of type int

<template<...> typename C Foo> // A template

<Concept Foo> // a constrained type

<Concept auto Foo> // a constrained value

P1141 specifies that in <Concept auto Foo> concept is specifically a type constraint.

It is for example possible to write <Unsigned auto N> but not <PowerOf2 auto N>.

This seems like a very artificial limitation as it makes sense for a value to be

constrained by either its value or its type.

Similarly, the paper removes the ability for a template template parameter to be constrained

without resorting to a require clause, in order to simplify the very much non-obvious syntax of

the working draft.

Which is a shame because previous adjective syntaxes proposed a solution for that

TemplateConstraint template <typename> typename Foo

Granted, template template parameters are rare and complex enough that having to resort to a require clause when using them isn’t terrible.

Still, it would have brought some symmetry and consistency to the syntax.

Which bring us to the next point

typename

I think one of the issues with the first adjective syntax papers is that people found <ConceptName typename T> overly verbose and a time where the committee was down with typename.

And of course, omitting typename is a good default as Bjarne S notices type parameter probably constitute 99% of cases.

So, it’s very fortunate that we don’t have to specify typename systematically.

Yet, I wish we could optionally put typename (as in <ConceptName typename T>) for teaching and consistency purposes.

It’s not a syntax that I expect seasoned developers would use, but it would make teaching easier.

we would have:

<typename Foo> // Any type

<auto Foo> // Any value

<Type Foo> // A value of type Type

<template<...> typename C Foo> // A template

<Concept typename Foo> // a constrained type

<Concept auto Foo> // a constrained value

<Concept template<...> typename Foo> // a constrained template

<Concept Foo> // a constrained type

In particular, notice the symetry in these three expression.

<Concept typename Foo> // a constrained type

<Concept auto Foo> // a constrained value

<Concept template<...> typename Foo> // a constrained template

That symmetry that is a core concept of the adjective syntaxes makes the teaching of concepts that much easier because we can actually say that a concept constrains a parameter declaration without having to alter that declaration. “Simply put a concept name on the left”. Of course, there would be restrictions, but those restrictions are logical

- Value concepts only apply to values

- Template concepts only apply to concepts

- Types concepts only apply to types… and values!

Terseness and good defaults are properties to strive for, however, consistencies and uniform grammar make learning the language (or the use of a new feature, in this case, concepts) easier.

To be perfectly clear, I believe <Concept Foo> to be a good default as a synonym of Concept typename Foo. And who knows, maybe someday we will be down with auto and template too.

Notice that in the declaration of a function return type P1141 allows both Concept auto and Concept. So why not allow both Concept and Concept typename in template type parameters?

These are minors issue in what I consider otherwise a very good solution.

Down with template!

The convenient syntaxes goal was never to make writing the STL or the Ranges library any easier to write. These libs very fined tuned, complex requirements where every parameter depends on the previous, or the next. And, as I like to say, if you have complex requirements, use a require clause.

Yet, it turns out that we often need to gives a name to a template type parameter, and that convenient syntaxes may not be convenient that often. That’s why both the Concept Lite and the “in place” syntax proposals had this type introducer syntax to actually give a name to deduced types, so they can be referred later.

I don’t like these syntaxes: They are completely novel (in any language) and they introduce dependencies between parameter and new types can be introduced virtually anywhere in the signature or the body of methods, which I believe would be hard to maintain or read. And, it’s important to remember when talking about syntax that code is meant to be read more than it is meant to be written.

So we are left of the following choices

- Do the

templatedance : template <typename T> const T & min(const T & a, const T & b);` - Using decltype (and getting it wrong) :

auto min(const T & a, decltype(a), b) -> decltype(a); - Using some kind of type introducer

auto min(const auto{T} & a, const T &b) -> const T&

Note that the last 2 syntaxes introduce dependencies between parameters declarations.

But… is there another solution? I think there is.

I had the following assumptions in mind as a starting point

- A lot of interest and work is being put in these convenient syntaxes.

- Most convenient syntaxes don’t use a

templatekeyword. - The most straight-forward way to introduce a type name is to introduce a template parameter :

template <typename T> void f() { /* Do whatever with T*/ }

I was also thinking about Lambdas. Lambdas have an interesting history. They started by not having any form of syntax support in C++11.

Then in C++17, they gained support for auto parameters. So in C++17, you can have [](auto foo){} but not void bar(auto foo){}.

People then realized that giving a name to the type of the deduced parameter might be useful, so in C++20, The following syntax was introduced.

[]<typename T>(T foo) {}

Now the type of foo has a name (T). the syntax for what goes into these <> is exactly the same that what goes into the template parameter list of a function.

Because it is a parameter list. But look at how unceremonious it is, while being immediately understandable by anyone familiar with C++.

So, I’ve started to wonder, can we just get rid of the template without introducing parsing ambiguities?

template <typename T> void f() would become <typename T> void f().

I found this to be asymetrical with use:

<typename T> void f();

f<int>();

and asymetric with lambda:

[]<typename T>(){}

<typename T> void f();

I then realized it would be more elegant to put the template parameter list after the function name:

void f<typename T>();

This feels very natural to me and reasonably terse. I felt very proud and smart to have come to this novel solution that nobody thought of. But then I opened my copy of Design and Evolution of C++ written by Bjarne Stroustrup in 1994:

As ever, syntax was a problem. Initially, I had aimed for a syntax in which a template argument was placed immediately after the template name:

class vector<class T> {

// . . .

};

However, this didn’t cleanly extend to function templates [Stroustrup, 1988b]:

’ ‘The function syntax at first glance also looks nicer without the extra keyword:

T& index<class T>(vector<T>& v, int i) {/*...* / }

There is typically no parallel (to class templates) in the usage, though, since function template arguments are not usually specified explicitly:

int i = index(vi,10);

char* p = index(vpc,29);

However, there appear to be nagging problems with this “simpler” syntax. It is

too clever. It is relatively hard to spot a template declaration in a program because

the template arguments are deeply embedded in the syntax of functions and

classes and the parsing of some function templates is a minor nightmare. It is possible

to write a C++ parser that handles function template declarations where a

template argument is used before it is defined, as in index () above. I know,

because I wrote one, but it is not easy nor does the problem appear amenable to

traditional parsing techniques. In retrospect, I think that not using a keyword and

not requiring a template argument to be declared before it is used would result in a

set of problems similar to those arising from the clever and convoluted C and C++

declarator syntax."

Using the final template syntax the declaration of index() becomes:

template<class T> T& index(vector<T>& v, int i) { /* ... */ }

At the time, I seriously discussed the possibility of providing a syntax that allowed the return value of a function to be placed after the arguments. For example

index<class T>(vector<T>& v, int i) return T& { /* ... */ }

index<class T>(vector<T>& v, int i) : T& {/*...* / }

This would solve the parsing problem, but most people like having a keyword to help

recognize templates, so that line of reasoning became redundant.

The <. . . > brackets were chosen in preference to parentheses because users

found them easier to read and because parentheses are overused in the C and C++

grammar. As it happens, Tom Pennnello proved that parentheses would have been

easier to parse, but that doesn’t change the key observation that (human) readers prefer

<.. . >.

Bjarne Stroustrup, Parameterized Types for C++, 1988

And what I did then, was to reinvent a 30 years old idea…

However, there are a lot of things to take away from this insightful quote.

One of the issue with this syntax was that in

T foo<typename T>();, T is used before it is declared. First, I don’t believe this

would add a lot (if any) complexity to a modern compiler, late parsing happening in quite a few places already.

But, most importantly, in C++11, we did introduce a trailing return syntax akin to the one Bjarne mentions:

auto foo() -> int ();.

The other concern regarding parsing ambiguities are resolved by always having a leading return type

(which can be auto).

At the time, templates were novels and people like having keywords for new features. In What – if anything – have we learned from C++?, Bjarne notices that:

For new features, people insist on LOUD explicit syntax For established features, people want terse notation

And indeed, it took quite a while for people to warm-up to the idea of a convenient, terse template declaration syntax.

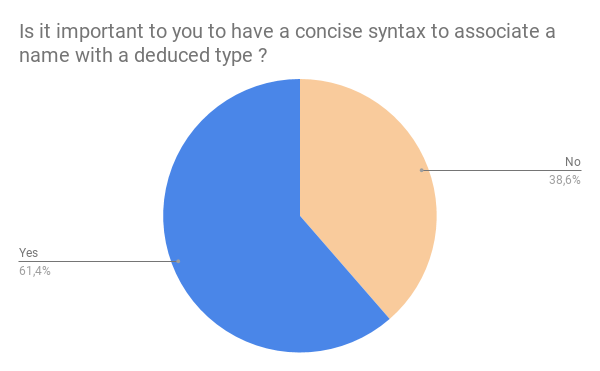

But, the time for a terser syntax has come, as shown by an increasing interest and an abundance of discussions in the past 5 years.

Later attempt focuses and shoveling everything into parameter declaration, which I believe is the wrong approach, and instead

getting rid of the template keyword would increase the terseness without resorting to novel confusing (In-Place)

or ambiguous (minimal solution) syntaxes.

And indeed, if the community and committee are willing to have functions template without any template parameter list at all, surely, having a shorter syntax for template parameters would be well received!

| C++20 | Proposed |

|---|---|

auto sort = []<typename RandomAccessIterator>

(RandomAccessIterator first, RandomAccessIterator second){}

template<class RandomAccessIterator> constexpr void sort

(RandomAccessIterator first, RandomAccessIterator last);

|

auto sort = []<typename RandomAccessIterator>

(RandomAccessIterator first, RandomAccessIterator second){}

constexpr void sort<class RandomAccessIterator>

(RandomAccessIterator first, RandomAccessIterator last);

|

Motivation, Rationale and design goals.

I propose that the template parameter list can be put immediately after a type name in types and function declaration,

instead of before the declaration. The template keyword is not used.

Why?

- Because people have expressed a desire for a terser function template declaration syntax

- Because it adds a lot of consistency and uniformity to the language, notably by making lambdas and functions obey the same grammar rules.

- This, in turn, makes the language easier to teach and learn.

- By forgoing the template keyword, template declaration feel less ceremonious, achieving a long-desired goal of some committee members to make generic programming more seamlessly integrated with non-generic programming.

Why not?

- I merely proposes to get rid of the

templatekeyword and shifting the template-parameter-list a few token to the left, which might be deemed not worth the trouble - We would have 2 syntaxes to declare a template parameter list

- Some questions remain, notably regarding potential parsing ambiguities involving template specialization.

What about P1141?

I am strongly in favor of P1141, and this means to complement it. If you need to constrain a function parameter, the syntax for function parameters introduced by P1141 will serve you nicely. If you need to introduce a constrained named type or need to specify a relation between multiple parameters, the syntax proposed here will be better. Note that the syntax for constrained template parameters proposed by P1141 would apply to what I am proposing here.

Is the world ready for a terser syntax?

I don’t know, it certainly looks that way.

In any case, if we are ready for an abbreviated syntax such as P1141, we should be willing to get rid of template in more places.

What about type introducers such as proposed by the “Concept In-Place Syntax” proposal?

My personal conviction is that it is a bad idea to be able to introduce types in a parameter declaration as it introducing dependencies between parameters and declarations, which hinder the ability to reason locally about the code. I see value in the “If you need to introduce a type, use a template parameter list”, which is how C++20’s generic lambdas were designed. Here, I propose a shorter syntax to introduce types that do not require a new syntax (it’s a familiar syntax made a bit terser).

Can it be made terser still?

Yes, you can use void f<class T>(){}; instead of void f<typename T>(){};

as these two keywords have had the same meaning in this context for quite a while.

Nothing terser?

I tend to think that terseness is a noble goal. Up to a point. Cramming too much information in too few keywords is done at the cost of teachability, consistency, and maintainability. These properties are tied together and at some point terseness becomes detrimental.

Functions and lambda

The following table compares lambdas as in the C++ WD and P1141 and functions as per the following proposal.

| C++20 Lambdas | Function template |

|---|---|

auto f = [](){}

auto f = []() -> int {}

auto f = [](const Containter auto &){}

auto f = []<typename T>(const T & a, const T & b){}

auto f = []<Regular T>(const T & a, const T & b){}

auto merge = [] |

void f(){}

auto f() -> int {}

auto f(const Containter auto &){}

auto f<typename T>(const T & a, const T & b){}

auto f<Regular T>(const T & a, const T & b){}

auto merge |

Unified Theory of Everything

/*A lambda*/

auto foo = [](int) -> void {}

/* A function */

auto foo(int) -> void {}

/* A function */

void foo(int);

/* A generic lambda */

auto foo = [](auto) -> void {}

/* A function template */

void foo(auto) {}

/* A generic lambda with a constrained parameter as per P1141 */

auto foo = [](const Container auto &) -> void {}

/* A function template with a constrained parameter as per P1141*/

auto foo(const Container auto &) -> void {}

auto foo(Container auto const &) -> void {}

/* A generic lambda with types introducers as per C++20*/

auto foo = []<typename T>(T t) -> void {}

/* A function template with a type introducer : proposed */

Bar foo<typename T>(T t);

/* A function call */

foo<int>();

/* A function template with a value template parameter */

auto foo<auto N>(T t) -> decltype(N) { return N * 1 ; }

/* Usage is symetric */

foo<42>();

/* A generic lambda with a constrained type introducer as per C++20*/

auto foo = []<Container T>(T & t) -> void {}

/* A function template with a constrained type introducer : proposed*/

void foo<Container T> (T & t){}

/* A generic lambda with a requires clause as per C++20*/

auto foo = []<Container T> requires EquallyComparable<T> (T & t) -> void {}

/* A function template with a requires clause : proposed*/

void foo<Container T> requires EquallyComparable<T> (T & t){}

/* A recursive lambda wg21.link/p0839 */

[]foo<typename T>(T v = 0) {

return (v > 0) foo(v - 1) : v;

}(1);

/* A variable */

auto bar = foo<int>();

/* A constrained variable as per P1141*/

Integral auto const bar = foo<int>();

/* Another constrained variable as per P1141, auto ommitted*/

Integral const bar = foo<int>();

/* A function with a constrained return type as per P1141*/

Sortable auto foo();

/* A function with a constrained return type as per P1141 */

auto foo() -> Sortable;

/* A function with a constrained return type as per P1141 */

Sortable foo();

/* Merge function */

auto merge<typename IN1, typename IN2, typename Out)

requires Mergeable<IN1,IN2,OUT>(IN1, IN1, IN2, IN2, OUT) -> Out;

/* Merge lambda */

auto merge = []<typename IN1, typename IN2, typename Out)

requires Mergeable<IN1,IN2,OUT>(IN1, IN1, IN2, IN2, OUT) -> Out;

/* Same type */

auto min<typename T>(const T&, const T&) -> const T&;

/* Template class declaration */

class vector<typename T> {};

/* Symetric use */

using string_vector = vector<string>;

/* Template Alias */

using my_vector<typename T> = vector<T>;

/* Concept declaration */

concept Everything<typename T> = true;

/* Symetrical use */

static_assert<Everything<int>()>;

/* Friend */

class A {

friend class B<class T>;

friend void f<class T>(T){ /* ... */ }

};

Potential issues and open questions

Can we have 2 template parameters list in the same declaration?

Aka, should template<typename T> void f<typename U>(); be valid ?

For me, the answer is clearly no. While I obviously see the benefit of having a terser syntax,

for the sake of maintainability and readability, I think a given declaration should either use a template-head

(template<typename T> or a template-parameter-list, but never both.)

Where to put the requires clause(s)?

In the Working Draft, there are two places where one can put a require clause. After the template parameter list preceding the declaration, and before trailing return type. Quoting the standard:

void f1(int a) requires true; // OK

auto f2(int a) -> bool requires true; // OK

// error: requires-clause precedes trailing-return-type

auto f3(int a) requires true -> bool;

And, as I’m proposing to have a second place to put a template parameter list, I wonder : Is it reasonable or useful to have two places where to put requires clauses? At the same time?

I am not, however, proposing to change that. There can be a trailing-requires-clause and a requires clauses after the template parameters list.

// OK in the WD: truer syntad have never been worded.

template <bool b = true> requires true bool f() -> requires true

// OK in the WD

[]<bool b = true> requires true () -> bool requires true {};

// Ok, as proposed

bool f<bool b = true> requires true () -> requires true {}

Because we do not allow 2 template parameter lists, the following are ill-formed:

// Ill-formed (one template parameters list is enough)

template <bool a> bool f<bool b>();

// Ill-formed !

template <bool a> requires true bool f<bool b> requires true();

// Stop it

template <bool a> requires true bool f<bool b> requires true() requires true;

Should a leading return type depending on a template parameter be valid?

The function template <typename T> T make_t(); can be rewritten auto make_t<typename T>() -> T;.

But should we allow T make_t<typename T>(); to be well-formed, ie to refer to a not-yet-declared type?

This would require delaying the parsing of the return type of all functions (except those that are preceded by a template-head ), until after the parsing of the template-parameter-list that may be present after the function name.

While I think this could be implemented, the complexity it would add may not be worth the trouble.

Using type before they have been declared also sets a precedent I’m not quite comfortable with.

The closest valid syntax to that I can think of is struct S* s;

Specialization

The proposed syntax has the potential to make template specialization easier, by putting the template parameter list closer to the related declaration.

Given

template <class T1> class A {

template <class T2> class B {

template <class T3> class C {};

};

};

This specialization

template <>

template <>

template <>

class A<int>::B<int>::C<int> {};

Can be rewritten as class A<int>::B<int>::C<int> {};, which is less verbose, while still being readable.

In fact, a compiler can diagnostic a missing template <>.

template <typename X> class D{};

class D<int>{};

//error: an explicit specialization must be preceded by 'template <>'

There may, however, be some issues.

For one, given class Foo<int>{};, a human reader, without context, can’t know whether Foo declares a template class with an int template

parameter or specialize Foo for ìnt.

Given the outcomes of numerous recent syntax-related discussions, I do expect that people will want a way to make that distinction.

But the compiler would also have to do some look ahead to distinguish declarations from specialization with nested types. The following example was provided by Tony V.E. While unambiguous, it requires a bit more look ahead:

struct T { ... };

Bar foo<typename T::type>(int t);

I think it might be reasonable not to allow specialization using this new syntax as a first approach, specialization can still be achieved using the current syntax.

Share on